Christmas

A Christian Meditation

Home / Christmas-a-christmas-meditation

‘And the Word became flesh and lived among us’.

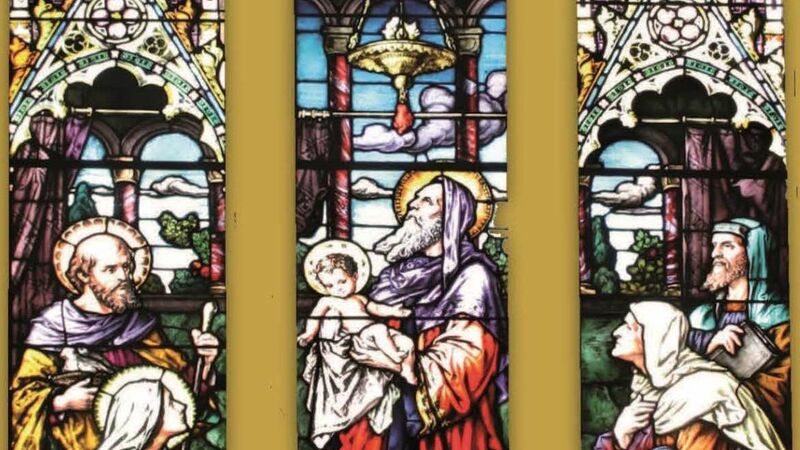

Asked about the best theologian I have heard I amazed my audience by answering, ‘A small child’. This was not an appeal to the Gospel passage about Jesus’ assertion of the primacy of a child’s place in the Kingdom of God. About twenty years ago as it was getting dark on Christmas day I went to the local church. A couple entered with their little boy who wandered around for a while and after his mother’s cajoling eventually came to stand at the crib. He climbed onto the pew that was placed at the front of the crib The scene before him was familiar, animals in the surrounding countryside, a couple like his parents, a child in a makeshift cot perhaps reminding him of a photo of himself as a baby. The star and angels would have been seasonal to his sight as the carols being piped were to his hearing. Silent for a few moments he suddenly asked for all to hear ‘But where is holy God?’ Inspecting a scene so seemingly human and natural he was in fact and hopefully through time in faith viewing what Gerald Manley Hopkins called ‘God’s infinity dwindled to infancy’. The child’s inquiry goes to the heart of the mystery of the Incarnation, pronounced on that day in the Gospel – ‘And the Word became flesh and lived among us’.

This incident calls to mind a passage from the Irish writer Frank O’Connor’s autobiography: One Christmas Santa Claus brought me a toy engine. As it was the only present I had received, I took it with me to the convent, and played with it on the floor while Mother and “the old nuns” discussed old times. But it was a young nun who brought us in to see the crib. When I saw the Holy Child in the manger I was very distressed, because little as I had, he had nothing at all. For me it was fresh proof of the incompetence of Santa Claus – an elderly man who hadn’t even remembered to give the Infant Jesus a toy and who should have been retired long ago. I asked the young nun politely if the Holy Child didn’t like toys, and she replied composedly enough: “Oh, he does, but his mother is too poor to afford them”. That settled it. My mother was poor too, but at Christmas she at least managed to buy me something, even if it was only a box of crayons. I distinctly remember getting into the crib and putting the engine between his outstretched arms. I probably showed him how to wind it as well, because a small baby like that would not be clever enough to know. I remember too the tearful feeling of reckless generosity with which I left him there in the nightly darkness of the chapel, clutching my toy engine to his chest’.[1]Entering into the lighted chapel, the child is immediately struck by the sight of the baby in the crib bereft of a Christmas present. There is no mention of the Magi and their munificent gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh which anyway, in the child’s assessment, would not have amounted to anything useful or enjoyable. The vision of the baby in the darkness equipped not only with the toy engine but also the expertise to empower it, fires the child’s imagination

Sentimentality surrenders to pathos in this passage. The sight of the child climbing into the crib, surrendering his own and only gift at Christmas while instructing the infant how to make it work for him, surpasses philanthropy. The child is not giving from his surplus, as if he has had a surfeit of pleasure and possessions. Like the poverty-stricken widow, whom Jesus ‘happened to notice putting two small coins into the treasury’ (Luke 21:1-2), the child parts with all he had to play with, a cost considerably higher for an only child. Not having an embarrassment of riches the child earns the encomium of King Lear to his daughter Cordelia, ‘Upon such sacrifices the gods themselves throw incense’. Applauding the innocence of his intervention to redeem the ineptitude, indeed inequality of Santa Claus, the child’s sacrifice of his toy engine is more than an example of and exhortation to Christmas charity. In the conjoined phrase of a contemporary of Frank O’Connor, the poet Patrick Kavanagh, this is ‘the wonder of a Christmas childhood’. In the words of his namesake, the English poet P J Kavanagh, we are invited ‘to imagine hugely’. The horizon of our imagining is the help, healing and hope that faith in the God who ‘so loved the world that he gave his only Son’ (John 3:16) holds out for us. Perhaps because it is particularly a time of memories, at Christmas we perceive the poignancy of our need for tenderness and togetherness. May the child in the crib, the compassionate Christ, communicate to us the ‘reckless generosity’ of God, ‘the Father of mercies’ (2 Cor 1:3), through the comfort and consolation of the Holy Spirit.

Dr Kevin O’Gorman SMA

[1]Frank O’Connor, An Only Child((London: Macmillan & Co Ltd, 1965), 136-137.

If you live outside Ireland, check out our dedicated area for international students.

Let’s talk

For Undergraduate queries: email admissions@spcm.ie.

For Postgraduate queries: email pgadmissions@spcm.ie.

For The Centre for Mission & Ministries queries, email: cmmadmissions@spcm.ie.